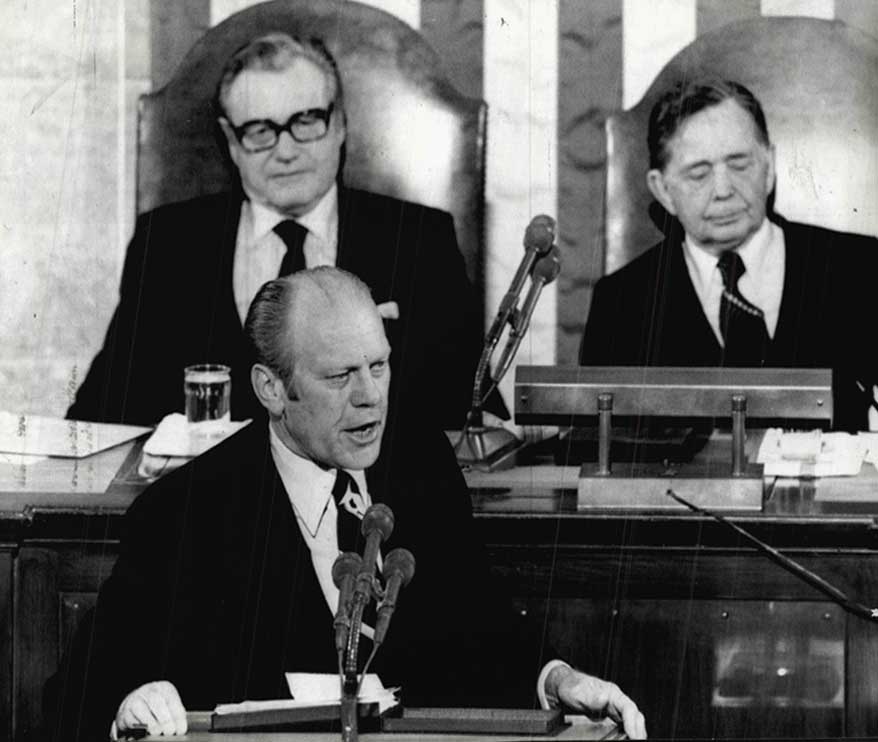

Pres. Gerald R. Ford, Jr. (D-MI) addresses a joint session of Congress on 10 April 1975. Behind him sit V. Pres. Nelson A. Rockefeller (R-NY) and Speaker of the House Carl B. Albert (D-OK).

My thanks to the University of Virginia’s Miller Center for their transcription of Pres. Gerald R. Ford, Jr.’s 10 April 1975 congressional address. Pictures shown are purely for educational purposes and no permission has been sought. If any mistakes are found, please let me know by contacting me here.

Mr. Speaker [Carl B. Albert (D-OK)], Mr. [Vice] President [Nelson A. Rockefeller (R-NY)], distinguished guests, my very good friends in the Congress, and fellow Americans:

I stand before you tonight after many agonizing hours in very solemn prayers for guidance by the Almighty. In my report on the state of the union in January [15 January 1975], I concentrated on two subjects which were uppermost in the minds of the American people: urgent actions for the recovery of our economy and a comprehensive program to make the United States independent of foreign sources of energy.

I thank the Congress for the action that it has taken thus far in my response for economic recommendations. I look forward to early approval of a national energy program to meet our country’s long-range and emergency needs in the field of energy.

Tonight it is my purpose to review our relations with the rest of the world in the spirit of candor and consultation which I have sought to maintain with my former colleagues and with our countrymen from the time that I took office. It is the first priority of my presidency to sustain and strengthen the mutual trust and respect which must exist among Americans and their government if we are to deal successfully with the challenges confronting us both at home and abroad.

The leadership of the United States of America since the end of World War II has sustained and advanced the security, well-being, and freedom of millions of human beings besides ourselves. Despite some setbacks, despite some mistakes, the United States has made peace a real prospect for us and for all nations. I know firsthand that the Congress has been a partner in the development and in the support of American foreign policy, which five presidents before me have carried forward with changes of course but not of destination.

The course which our country chooses in the world today has never been of greater significance for ourselves as a nation and for all mankind. We build from a solid foundation. Our alliances with great industrial democracies in Europe, North America, and Japan remain strong with a greater degree of consultation and equity than ever before.

With the Soviet Union we have moved across a broad front toward a more stable, if still competitive, relationship. We have begun to control the spiral of strategic nuclear armaments. After two decades of mutual estrangement, we have achieved an historic opening with the People’s Republic of China.

In the best American tradition, we have committed, often with striking success, our influence and good offices to help contain conflicts and settle disputes in many, many regions of the world. We have, for example, helped the parties of the Middle East take the first steps toward living with one another in peace.

We have opened a new dialog with Latin America, looking toward a healthier hemispheric partnership. We are developing closer relations with the nations of Africa. We have exercised international leadership on the great new issues of our interdependent world, such as energy, food, environment, and the law of the sea.

The American people can be proud of what their nation has achieved and helped others to accomplish, but we have from time to time suffered setbacks and disappointments in foreign policy. Some were events over which we had no control; some were difficulties we imposed upon ourselves.

We live in a time of testing and of a time of change. Our world – a world of economic uncertainty, political unrest, and threats to the peace – does not allow us the luxury of abdication or domestic discord.

I recall quite vividly the words of President Truman to the congress when the United States faced a far greater challenge at the end of the Second World War. If I might quote: “If we falter in our leadership, we may endanger the peace of the world, and we shall surely endanger the welfare of this nation [President Harry S Truman (D-MO), Congressional Address (12 March 1947)].”

President Truman’s resolution must guide us today. Our purpose is not to point the finger of blame, but to build upon our many successes, to repair damage where we find it, to recover our balance, to move ahead as a united people. Tonight is a time for straight talk among friends, about where we stand and where we are going.

A vast human tragedy has befallen our friends in Viêt Nam and Cambodia. Tonight I shall not talk only of obligations arising from legal documents. Who can forget the enormous sacrifices of blood, dedication, and treasure that we made in Viêt Nam?

Under five Presidents and 12 Congresses, the United States was engaged in Indochina. Millions of Americans served, thousands died, and many more were wounded, imprisoned, or lost. Over $150 billion have been appropriated for that war by the Congress of the United States. And after years of effort, we negotiated, under the most difficult circumstances, a settlement which made it possible for us to remove our military forces and bring home with pride our American prisoners. This settlement, if its terms had been adhered to, would have permitted our South Viêtnamese ally, with our material and moral support, to maintain its security and rebuild after two decades of war.

The chances for an enduring peace after the last American fighting man left Viêt Nam in 1973 rested on two publicly stated premises: first, that if necessary, the United States would help sustain the terms of the Paris accords it signed two years ago, and second, that the United States would provide adequate economic and military assistance to South Viêt Nam.

Let us refresh our memories for just a moment. The universal consensus in the United States at that time, late-1972, was that if we could end our own involvement and obtain the release of our prisoners, we would provide adequate material support to South Viêt Nam. The North Viêtnamese, from the moment they signed the Paris accords [27 January 1973], systematically violated the cease-fire and other provisions of that agreement. Flagrantly disregarding the ban on the infiltration of troops, the North Viêtnamese illegally introduced over 350,000 men into the South. In direct violation of the agreement, they sent in the most modern equipment in massive amounts. Meanwhile, they continued to receive large quantities of supplies and arms from their friends.

In the face of this situation, the United States – torn as it was by the emotions of a decade of war – was unable to respond. We deprived ourselves by law of the ability to enforce the agreement, thus giving North Viêt Nam assurance, that it could violate that agreement with impunity [Case-Church Amendment of 1973]. Next, we reduced our economic and arms aid to South Viêt Nam [Foreign Assistance Act of 1974]. Finally, we signaled our increasing reluctance to give any support to that nation struggling for its survival.

Encouraged by these developments, the North Viêtnamese, in recent months, began sending even their reserve divisions into South Viêt Nam. Some 20 divisions, virtually their entire army, are now in South Viêt Nam.

The government of South Viêt Nam, uncertain of further American assistance, hastily ordered a strategic withdrawal to more defensible positions. This extremely difficult maneuver, decided upon without consultations, was poorly executed, hampered by floods of refugees, and thus led to panic. The results are painfully obvious and profoundly moving.

In my first public comment on this tragic development, I called for a new sense of national unity and purpose. I said I would not engage in recriminations or attempts to assess the blame. I reiterate that tonight.

In the same spirit, I welcome the statement of the distinguished majority leader of the United States senate earlier this week, and I quote: “It is time for the Congress and the president to work together in the area of foreign as well as domestic policy [Sen. Mike J. Mansfield (D-MT)].”

So, let us start afresh.

I am here to work with the Congress. In the conduct of foreign affairs, presidential initiative and ability to act swiftly in emergencies are essential to our national interest.

With respect to North Viêt Nam, I call upon Hanoi – and ask the Congress to join with me in this call – to cease military operations immediately and to honor the terms of the Paris agreement.

The United States is urgently requesting the signatories of the Paris conference to meet their obligations to use their influence to halt the fighting and to enforce the 1973 accords. Diplomatic notes to this effect have been sent to all members of the Paris conference, including the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China.

The situation in South Viêt Nam and Cambodia has reached a critical phase requiring immediate and positive decisions by this Government. The options before us are few and the time is very short.

On the one hand, the United States could do nothing more: let the government of South Viêt Nam save itself and what is left of its territory, if it can; let those South Viêtnamese civilians who have worked with us for a decade or more save their lives and their families, if they can; in short, shut our eyes and wash our hands of the whole affair, if we can.

Or, on the other hand, I could ask the Congress for authority to enforce the Paris accords with our troops and our tanks and our aircraft and our artillery and carry the war to the enemy.

There are two narrower options:

First, stick with my January request that congress appropriate $300 million for military assistance for South Viêt Nam and seek additional funds for economic and humanitarian purposes.

Or, increase my requests for both emergency military and humanitarian assistance to levels which, by best estimates, might enable the South Viêtnamese to stem the onrushing aggression, to stabilize the military situation, permit the chance of a negotiated political settlement between the North and South Viêtnamese, and if the very worst were to happen, at least allow the orderly evacuation of Americans and endangered South Viêtnamese to places of safety. Let me now state my considerations and my conclusions.

I have received a full report from General Weyand [GEN Frederick C. Weyand, USA], whom I sent to Viêt Nam to assess the situation. He advises that the current military situation is very critical, but that South Viêt Nam is continuing to defend itself with the resources available. However, he feels that if there is to be any chance of success for their defense plan, South Viêt Nam needs urgently an additional $722 million in very specific military supplies from the United States. In my judgment, a stabilization of the military situation offers the best opportunity for a political solution.

I must, of course, as I think each of you would, consider the safety of nearly 6,000 Americans who remain in South Viêt Nam and tens of thousands of South Viêtnamese employees of the United States government, of news agencies, of contractors and businesses for many years whose lives, with their dependents, are in very grave peril. There are tens of thousands of other South Viêtnamese intellectuals, professors, teachers, editors, and opinion leaders who have supported the South Viêtnamese cause and the alliance with the United States to whom we have a profound moral obligation.

I am also mindful of our posture toward the rest of the world and, particularly, of our future relations with the free nations of Asia. These nations must not think for a minute that the United States is pulling out on them or intends to abandon them to aggression.

I have therefore concluded that the national interests of the United States and the cause of world stability require that we continue to give both military and humanitarian assistance to the South Viêtnamese.

Assistance to South Viêt Nam at this stage must be swift and adequate. Drift and indecision invite far deeper disaster. The sums I had requested before the major North Viêtnamese offensive and the sudden South Viêtnamese retreat are obviously inadequate. Half-hearted action would be worse than none. We must act together and act decisively.

I am therefore asking the Congress to appropriate without delay $722 million for emergency military assistance and an initial sum of $250 million for economic and humanitarian aid for South Viêt Nam.

The situation in South Viêt Nam is changing very rapidly, and the need for emergency food, medicine, and refugee relief is growing by the hour. I will work with the Congress in the days ahead to develop humanitarian assistance to meet these very pressing needs.

Fundamental decency requires that we do everything in our power to ease the misery and the pain of the monumental human crisis which has befallen the people of Viêt Nam. Millions have fled in the face of the Communist onslaught and are now homeless and are now destitute. I hereby pledge in the name of the American people that the United States will make a maximum humanitarian effort to help care for and feed these hopeless victims.

And now I ask the Congress to clarify immediately its restrictions on the use of U.S. military forces in Southeast Asia for the limited purposes of protecting American lives by ensuring their evacuation, if this should be necessary. And I also ask prompt revision of the law to cover those Viêtnamese to whom we have a very special obligation and whose lives may be endangered should the worst come to pass.

I hope that this authority will never have to be used, but if it is needed, there will be no time for congressional debate. Because of the gravity of the situation, I ask the Congress to complete action on all of these measures not later than April 19.

In Cambodia, the situation is tragic. The United States and the Cambodian government have each made major efforts, over a long period and through many channels, to end that conflict. But because of their military successes, steady external support, and their awareness of American legal restrictions, the communist side has shown no interest in negotiation, compromise, or a political solution. And yet, for the past 3 months, the beleaguered people of Phnom Penh have fought on, hoping against hope that the United States would not desert them, but instead provide the arms and ammunition they so badly needed.

I have received a moving letter from the new acting President of Cambodia, Saukham Khoy, and let me quote it for you:

“Dear Mr. President,” he wrote, “As the American congress reconvenes to reconsider your urgent request for supplemental assistance for the Khmer Republic, I appeal to you to convey to the American legislators our plea not to deny these vital resources to us, if a nonmilitary solution is to emerge from this tragic five-year-old conflict.

“To find a peaceful end to the conflict we need time. I do not know how much time, but we all fully realize that the agony of the Khmer people cannot and must not go on much longer. However, for the immediate future, we need the rice to feed the hungry and the ammunition and the weapons to defend ourselves against those who want to impose their will by force. A denial by the American people of the means for us to carry on will leave us no alternative but inevitably abandoning our search for a solution which will give our citizens some freedom of choice as to their future. For a number of years now the Cambodian people have placed their trust in America. I cannot believe that this confidence was misplaced and that suddenly America will deny us the means which might give us a chance to find an acceptable solution to our conflict.”

This letter speaks for itself. In January, I requested food and ammunition for the brave Cambodians, and I regret to say that as of this evening, it may be soon too late.

Members of the Congress, my fellow Americans, this moment of tragedy for Indochina is a time of trial for us. It is a time for national resolve.

It has been said that the United States is over-extended, that we have too many commitments too far from home, that we must reexamine what our truly vital interests are and shape our strategy to conform to them. I find no fault with this as a theory, but in the real world such a course must be pursued carefully and in close coordination with solid progress toward overall reduction in worldwide tensions.

We cannot, in the meantime, abandon our friends while our adversaries support and encourage theirs. We cannot dismantle our defenses, our diplomacy, or our intelligence capability while others increase and strengthen theirs.

Let us put an end to self-inflicted wounds. Let us remember that our national unity is a most priceless asset. Let us deny our adversaries the satisfaction of using Viêt Nam to pit Americans against Americans. At this moment, the United States must present to the world a united front.

Above all, let’s keep events in Southeast Asia in their proper perspective. The security and the progress of hundreds of millions of people everywhere depend importantly on us.

Let no potential adversary believe that our difficulties or our debates mean a slackening of our national will. We will stand by our friends, we will honor our commitments, and we will uphold our country’s principles.

The American people know that our strength, our authority, and our leadership have helped prevent a third world war for more than a generation. We will not shrink from this duty in the decades ahead.

Let me now review with you the basic elements of our foreign policy, speaking candidly about our strengths and some of our difficulties.

We must, first of all, face the fact that what has happened in Indochina has disquieted many of our friends, especially in Asia. We must deal with this situation promptly and firmly. To this end, I have already scheduled meetings with the leaders of Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Indonesia, and I expect to meet with the leaders of other Asian countries as well.

A key country in this respect is Japan. The warm welcome I received in Japan last November vividly symbolized for both our peoples the friendship and the solidarity of this extraordinary partnership. I look forward, as I am sure all of you do, with very special pleasure to welcoming the Emperor when he visits the United States later this year.

We consider our security treaty with Japan the cornerstone of stability in the vast reaches of Asia and the Pacific. Our relations are crucial to our mutual well-being. Together, we are working energetically on the international multilateral agenda in trade, energy, and food. We will continue the process of strengthening our friendship, mutual security, and prosperity.

Also, of course, of fundamental importance is our mutual security relationship with the Republic of Korea, which I reaffirmed on my recent visit.

Our relations with Europe have never been stronger. There are no peoples with whom America’s destiny has been more closely linked. There are no peoples whose friendship and cooperation are more needed for the future. For none of the members of the Atlantic community can be secure, none can prosper, none can advance unless we all do so together. More than ever, these times demand our close collaboration in order to maintain the secure anchor of our common security in this time of international riptides, to work together on the promising negotiations with our potential adversaries, to pool our energies on the great new economic challenge that faces us.

In addition to this traditional agenda, there are new problems involving energy, raw materials, and the environment. The Atlantic nations face many and complex negotiations and decisions. It is time to take stock, to consult on our future, to affirm once again our cohesion and our common destiny. I therefore expect to join with the other leaders of the Atlantic Alliance at a Western summit in the very near future.

Before this NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] meeting, I earnestly ask the Congress to weigh the broader considerations and consequences of its past actions on the complex Greek-Turkish dispute over Cyprus. Our foreign policy cannot be simply a collection of special economic or ethnic or ideological interests. There must be a deep concern for the overall design of our international actions. To achieve this design for peace and to assure that our individual acts have some coherence, the executive must have some flexibility in the conduct of foreign policy.

United States military assistance to an old and faithful ally, Turkey, has been cut off by action of the Congress. This has imposed an embargo on military purchases by Turkey, extending even to items already paid for – an unprecedented act against a friend. These moves, I know, were sincerely intended to influence Turkey in the Cyprus negotiations. I deeply share the concern of many citizens for the immense human suffering on Cyprus. I sympathize with the new democratic government in Greece. We are continuing our earnest efforts to find equitable solutions to the problems which exist between Greece and Turkey. But the result of the congressional action has been to block progress towards reconciliation, thereby prolonging the suffering on Cyprus, to complicate our ability to promote successful negotiations, to increase the danger of a broader conflict.

Our longstanding relationship with Turkey is not simply a favor to Turkey; it is a clear and essential mutual interest. Turkey lies on the rim of the Soviet Union and at the gates of the Middle East. It is vital to the security of the eastern Mediterranean, the southern flank of Western Europe, and the collective security of the Western alliance. Our US military bases in Turkey are as critical to our own security as they are to the defense of NATO.

I therefore call upon the Congress to lift the American arms embargo against our Turkish ally by passing the bipartisan Mansfield-Scott bill now before the Senate [Sen. Mike J. Mansfield (D-MT) and Sen. Hugh D. Scott, Jr. (R-PA)]. Only this will enable us to work with Greece and Turkey to resolve the differences between our allies. I accept and indeed welcome the bill’s requirement for monthly reports to the Congress on progress toward a Cyprus settlement, but unless this is done with dispatch, forces may be set in motion within and between the two nations which could not be reversed.

At the same time, in order to strengthen the democratic government of Greece and to reaffirm our traditional ties with the people of Greece, we are actively discussing a program of economic and military assistance with them. We will shortly be submitting specific requests to the Congress in this regard.

A vital element of our foreign policy is our relationship with the developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. These countries must know that America is a true, that America is a concerned friend, reliable both in word and deed.

As evidence of this friendship, I urge the Congress to reconsider one provision of the 1974 trade act which has had an unfortunate and unintended impact on our relations with Latin America, where we have such a long tie of friendship and cooperation. Under this legislation, all members of OPEC [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] were excluded from our generalized system of trade preferences. This, unfortunately, punished two South American friends, Ecuador and Venezuela, as well as other OPEC nations, such as Nigeria and Indonesia, none of which participated in last year’s oil embargo. This exclusion has seriously complicated our new dialog with our friends in this hemisphere. I therefore endorse the amendments which have been introduced in the Congress to provide executive authority to waive those restrictions on the trade act that are incompatible with our national interest.

The interests of America as well as our allies are vitally affected by what happens in the Middle East. So long as the state of tension continues, it threatens military crisis, the weakening of our alliances, the stability of the world economy, and confrontation with the nuclear super powers. These are intolerable risks.

Because we are in the unique position of being able to deal with all the parties, we have, at their request, been engaged for the past year and a half in the peacemaking effort unparalleled in the history of the region. Our policy has brought remarkable successes on the road to peace. Last year, two major disengagement agreements were negotiated and implemented with our help. For the first time in 30 years, a process of negotiation on the basic political issues was begun and is continuing.

Unfortunately, the latest efforts to reach a further interim agreement between Israel and Egypt have been suspended. The issues dividing the parties are vital to them and not amenable to easy and to quick solutions. However, the United States will not be discouraged.

The momentum toward peace that has been achieved over the last 18 months must and will be maintained. The active role of the United States must and will be continued. The drift toward war must and will be prevented.

I pledge the United States to a major effort for peace in the Middle East, an effort which I know has the solid support of the American people and their Congress. We are now examining how best to proceed. We have agreed in principle to reconvene the Geneva conference. We are prepared as well to explore other forums. The United States will move ahead on whatever course looks most promising, either towards an overall settlement or interim agreements, should the parties themselves desire them. We will not accept stagnation or stalemate with all its attendant risks to peace and prosperity and to our relations in and outside of the region.

The national interest and national security require as well that we reduce the dangers of war. We shall strive to do so by continuing to improve our relations with potential adversaries.

The United States and the Soviet Union share an interest in lessening tensions and building a more stable relationship. During this process, we have never had any illusions. We know that we are dealing with a nation that reflects different principles and is our competitor in many parts of the globe. Through a combination of firmness and flexibility, the United States, in recent years, laid the basis of a more reliable relationship, founded on mutual interest and mutual restraint. But we cannot expect the Soviet Union to show restraint in the face of the United States’ weakness or irresolution.

As long as I am president, America will maintain its strength, its alliances, and its principles as a prerequisite to a more peaceful planet. As long as I am president, we will not permit detente to become a license to fish in troubled waters. Détente must be – and, I trust, will be – a two-way relationship.

Central to US-Soviet relations today is the critical negotiation to control strategic nuclear weapons. We hope to turn the Vladivostok agreements into a final agreement this year at the time of General Secretary Brezhnev’s [Leonid I. Brezhnev] visit to the United States. Such an agreement would, for the first time, put a ceiling on the strategic arms race. It would mark a turning point in postwar history and would be a crucial step in lifting from mankind the threat of nuclear war.

Our use of trade and economic sanctions as weapons to alter the internal conduct of other nations must also be seriously reexamined. However well-intentioned the goals, the fact is that some of our recent actions in the economic field have been self-defeating, they are not achieving the objectives intended by the Congress, and they have damaged our foreign policy.

The Trade Act of 1974 prohibits most-favored-nation treatment, credit and investment guarantees and commercial agreements with the Soviet Union so long as their emigration policies fail to meet our criteria. The Soviet Union has therefore refused to put into effect the important 1972 trade agreement between our two countries.

As a result, Western Europe and Japan have stepped into the breach. Those countries have extended credits to the Soviet Union exceeding $8 billion in the last 6 months. These are economic opportunities, jobs, and business which could have gone to Americans.

There should be no illusions about the nature of the Soviet system, but there should be no illusions about how to deal with it. Our belief in the right of peoples of the world freely to emigrate has been well demonstrated. This legislation, however, not only harmed our relations with the Soviet Union but seriously complicated the prospects of those seeking to emigrate. The favorable trend, aided by quiet diplomacy, by which emigration increased from 400 in 1968 to over 33,000 in 1973 has been seriously set back. Remedial legislation is urgently needed in our national interest.

With the People’s Republic of China, we are firmly fixed on the course set forth in the Shanghai Communique [1972]. Stability in Asia and the world require our constructive relations with one-fourth of the human race. After two decades of mutual isolation and hostility, we have, in recent years, built a promising foundation. Deep differences in our philosophy and social systems will endure, but so should our mutual long-term interests and the goals to which our countries have jointly subscribed in Shanghai. I will visit China later this year to reaffirm these interests and to accelerate the improvement in our relations. And I was glad to welcome the distinguished speaker [Carl B. Albert (D-OK)] and the distinguished minority leader of the House [Sen. Hugh D. Scott, Jr. (R-PA)] back today from their constructive visit to the People’s Republic of China.

Let me talk about new challenges. The issues I have discussed are the most pressing of the traditional agenda on foreign policy, but ahead of us also is a vast new agenda of issues in an interdependent world. The United States, with its economic power, its technology, its zest for new horizons, is the acknowledged world leader in dealing with many of these challenges.

If this is a moment of uncertainty in the world, it is even more a moment of rare opportunity.

We are summoned to meet one of man’s most basic challenges: hunger. At the World Food Conference last November in Rome, the United States outlined a comprehensive program to close the ominous gap between population growth and food production over the long term. Our technological skill and our enormous productive capacity are crucial to accomplishing this task.

The old order in trade, finance, and raw materials is changing and American leadership is needed in the creation of new institutions and practices for worldwide prosperity and progress.

The world’s oceans, with their immense resources and strategic importance, must become areas of cooperation rather than conflict. American policy is directed to that end.

Technology must be harnessed to the service of mankind while protecting the environment. This, too, is an arena for American leadership.

The interests and the aspirations of the developed and developing nations must be reconciled in a manner that is both realistic and humane. This is our goal in this new era.

One of the finest success stories in our foreign policy is our cooperative effort with other major energy-consuming nations. In little more than a year, together with our partners, we have created the International Energy Agency; we have negotiated an emergency sharing arrangement which helps to reduce the dangers of an embargo; we have launched major international conservation efforts; we have developed a massive program for the development of alternative sources of energy.

But the fate of all of these programs depends crucially on what we do at home. Every month that passes brings us closer to the day when we will be dependent on imported energy for 50 percent of our requirements. A new embargo under these conditions could have a devastating impact on jobs, industrial expansion, and inflation at home. Our economy cannot be left to the mercy of decisions over which we have no control. And I call upon the Congress to act affirmatively.

In a world where information is power, a vital element of our national security lies in our intelligence services. They are essential to our nation’s security in peace as in war. Americans can be grateful for the important but largely unsung contributions and achievements of the intelligence services of this nation.

It is entirely proper that this system be subject to congressional review. But a sensationalized public debate over legitimate intelligence activities is a disservice to this nation and a threat to our intelligence system. It ties our hands while our potential enemies operate with secrecy, with skill, and with vast resources. Any investigation must be conducted with maximum discretion and dispatch to avoid crippling a vital national institution.

Let me speak quite frankly to some in this chamber and perhaps to some not in this chamber. The Central Intelligence Agency has been of maximum importance to presidents before me. The Central Intelligence Agency has been of maximum importance to me. The Central Intelligence Agency and its associated intelligence organizations could be of maximum importance to some of you in this audience who might be president at some later date. I think it would be catastrophic for the Congress or anyone else to destroy the usefulness by dismantling, in effect, our intelligence systems upon which we rest so heavily.

Now, as Congress oversees intelligence activities, it must, of course, organize itself to do so in a responsible way. It has been traditional for the executive to consult with the Congress through specially protected procedures that safeguard essential secrets. But recently, some of those procedures have altered in a way that makes the protection of vital information very, very difficult. I will say to the leaders of the Congress, the House and the Senate, that I will work with them to devise procedures which will meet the needs of the Congress for review of intelligence agency activities and the needs of the nation for an effective intelligence service.

Underlying any successful foreign policy is the strength and the credibility of our defense posture. We are strong and we are ready and we intend to remain so. Improvement of relations with adversaries does not mean any relaxation of our national vigilance. On the contrary, it is the firm maintenance of both strength and vigilance that makes possible steady progress toward a safer and a more peaceful world.

The national security budget that I have submitted is the minimum the United States needs in this critical hour. The Congress should review it carefully, and I know it will. But it is my considered judgment that any significant reduction, revision, would endanger our national security and thus jeopardize the peace.

Let no ally doubt our determination to maintain a defense second to none, and let no adversary be tempted to test our readiness or our resolve.

History is testing us today. We cannot afford indecision, disunity, or disarray in the conduct of our foreign affairs. You and I can resolve here and now that this nation shall move ahead with wisdom, with assurance, and with national unity.

The world looks to us for the vigor and for the vision that we have demonstrated so often in the past in great moments of our national history. And as I look down the road, I see a confident America, secure in its strengths, secure in its values, and determined to maintain both. I see a conciliatory America, extending its hand to allies and adversaries alike, forming bonds of cooperation to deal with the vast problems facing us all. I see a compassionate America, its heart reaching out to orphans, to refugees, and to our fellow human beings afflicted by war, by tyranny, and by hunger.

As president, entrusted by the Constitution with primary responsibility for the conduct of our foreign affairs, I renew the pledge I made last August to work cooperatively with the Congress. I ask that the Congress help to keep America’s word good throughout the world. We are one Nation, one government, and we must have one foreign policy.

In an hour far darker than this, Abraham Lincoln [R-IL] told his fellow citizens, and I quote: “We cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us.”

We who are entrusted by the people with the great decisions that fashion their future can escape neither responsibilities nor our consciences. By what we do now, the world will know our courage, our constancy, and our compassion.

The spirit of America is good and the heart of America is strong. Let us be proud of what we have done and confident of what we can do. And may God ever guide us to do what is right.

Thank you.